RaMell Ross on the Oscar-nominated “Nickel Boys” and why the film’s impact matters more to him than trophies.

“Nickel Boys” may not have taken home an Oscar last night, but for director Ramell Ross, working on the film was about more than just awards—it was about impact.

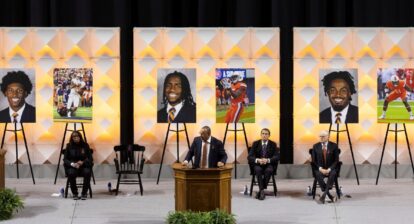

“It’s tough because, you know, one wants to think that awards don’t matter. Like, you don’t make stuff for awards. We’re not thinking about any awards when we’re making and working on the project,” Ross shared in a sit-down with theGrio. “The disposition I had [when working on the film] was, ‘If the film is ignored, if the film is not liked, or if the film is not appreciated, the intent of it is still so righteous—to give the Dozier School boys life and make a film that’s about [Elwood] living more than it is about him dying.”

For Ross, the value of “Nickel Boys” comes from its purpose, not its accolades. Acknowledging the challenges of bringing stories like this to the screen and presenting “Black folks’ point of view in cinema,” he admits that the awards conversation can be “really unnerving and stressful, but all for good intent.”

“Now that we’re in the awards conversation, you can’t help but want to win them,” he continued. “Especially if you get nominated for an Oscar, the Dozier School boys’ story will reach 200 million more people. This is not a fiction story. This is not a film made for entertainment. The film is made to participate in the entertainment industry, but it’s about something, and the form of the film is trying to say something.”

And it certainly does. Some movies entertain. Others educate. Then there are the ones that linger long after the credits roll, and “Nickel Boys” is the latter. Starring Aunjanue Ellis-Taylor, Ethan Herisse, and Brandon Wilson, the film adaptation of Colson Whitehead’s novel unveils the harrowing reality of the Nickel Academy, a reform school built on cruelty and systemic racism. Viewers follow Elwood Curtis, a bright young Black boy in 1960s Florida, whose dreams of college and a better future are shattered after one mistake lands him in an abusive institution. As he struggles to survive within the academy’s unforgiving walls, he forms a complex but necessary bond with Turner, a fellow inmate who challenges his unwavering belief in justice. Just as Turner and Elwood’s friendship becomes a beacon of hope in an otherwise grim reality, Ross approached the film as a “celebration of their lives by exploring the darker moments.”

“I think Elwood and Turner each represent one side of Colson. He [even] said this in interviews. It’s a kind of conversation between himself—cynicism and optimism as extremes. And so it kind of becomes the same thing for me. I see myself in both of them,” Ross explained. “Turner and Elwood probably [reflect] all people. Do we think it’s possible for us to do X, Y, or Z, or do I think I should just not have my hopes up because, most often, dreams fail? And this is even outside of race or any sort of political goal. I think, fundamentally, those two characters represent the two sides of everyone in terms of their futures and possibilities.”

Movies often transport audiences to different worlds—fictional, historical, or otherwise—through storytelling. But Ross doesn’t just tell this story; he immerses viewers in it. Through hauntingly intimate cinematography and a raw, first-person perspective, Ross pulls the audience directly into the boys’ world, making every moment feel urgent and inescapable. The film alternates between Elwood and Turner’s unique POVs, honing in on little details and only showing what is in each character’s gaze. The result is a visually striking experience that mirrors the perspective of a child—constantly observing, hearing, and sensing, but not always fully understanding.

“All people are point of view. Like, that’s the only way that we know the world, in fact. So in trying to think about the way that [characters] felt, it [was] almost as easy as just making an image from a singular point of view because it aligns so much with the way that we’ve seen the world that [viewers] are gonna draw connections,” Ross said, explaining his approach to conveying emotion. Part of that magic came from the writing process. Ross and co-writer Jocelyn Barnes were reportedly very intentional about “writing visually” to create an organic connection with the audience.

Beyond being a bold artistic choice, Ross’ filming style also seeks to redefine the relationship between people of color and the camera.

“To me, one strategy is making images from our point of view, not towards us. Normally, cameras go into the Black community. [But] the Black community isn’t often with the camera [or placed] at the center of the world [where] everything else is the other,” he explained. “So if you take that literally, and you give the camera to our characters—the Dozier School boys, the Nickel Boys—then you’re dealing with authorship. You’re placing our subjectivity, a character’s subjectivity, as the central organizing language of the film.”

“There’s nothing that is not understood through the way that they look at it, and that seems like a pretty beautiful thing, specifically for young kids who have passed away and didn’t quite have an opportunity for people to understand their subjectivity,” he continued.

Now the winner of three NAACP Image Awards, Ross says his approach to storytelling prioritizes audience experience above all else. He hopes others will begin to adopt a similar mindset.

“I think making a film and making a TV show and using images illustratively and telling the story through images is different from having the audience experience the narrative through images. You know, they’re two completely different things. One image is telling you something; the other, you’re participating in the meaning-making of it, and you’re negotiating the language of the form and the language of the narrative as you watch,” he said. “To me, that type of experience is what we experience in real life, and I think that’s how we come to conclusions that are effective, that makes us lean towards action and change… So I’m hoping that we begin to think more about experience creation in cinema as much as the narratives that are being told.”

!function(){var g=window;g.googletag=g.googletag||{},g.googletag.cmd=g.googletag.cmd||[],g.googletag.cmd.push(function(){g.googletag.pubads().setTargeting(“has-featured-video”,”true”)})}();

More must-reads: